D2X | Modern C++ Core Language Features - "A C++ tutorial project focused on practical"

Goals

[Master]- Core language features of Modern C++ and their usage scenarios[Master]- The ability to identify and debug issues using compiler error messages[Familiarize]- The ability to solve unfamiliar C++ problems using documentation and cppreference[Understand]- How to participate in the technical community — using open-source projects, asking questions, joining discussions, or contributing

Quick Start

Try

Code -> Book -> Video -> X -> Code

Interactive Code Practice (Online)

click the button below to automatically complete the configuration in the cloud and enter the practice code detection mode

Interactive Code Practice (Local)

click to view xlings installation command

Linux/MacOS

curl -fsSL https://d2learn.org/xlings-install.sh | bash

Windows - PowerShell

irm https://d2learn.org/xlings-install.ps1.txt | iex

tips: xlings -> details

xlings install d2x:mcpp-standard

cd mcpp-standard

d2x checker

Community

- groups: mcpp forum

- forum: issues feedback, practice code, technical discussions

- community activities: 📣 MSCP - mcpp project learning and contributor training program

Note: Complex issues (technical, environment setup, etc.) are recommended to be posted on the forum and detailed description of the problem can be more effective in problem solving and reuse.

Contributing

- Community Communication: Report issues, participate in community discussions, and help new users solve problems.

- Project Maintenance and Development: Participate in community issue resolution, bug fixes, multilingual support, join the MSCP activity group, and develop and optimize new features and modules.

📑License & CLA

- This project welcomes free use and distribution! You may use, modify, and share the code and documentation in this project free under the Apache License 2.0 and CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 licenses.

- If you would like to contribute code or documentation, please read the Contributor License Agreement (CLA) first.

👥Contributors

Preface

mcpp-standard is an open-source tutorial project focused on Modern C++ Core Language Features with an emphasis on hands-on coding practice. The project structure follows the [Book + Video + Code + X] model, providing users with online e-books, corresponding instructional videos, accompanying practice code, as well as discussion forums and regular learning activities.

Language Support

Activities | 📣 MSCP - mcpp Project Learning and Contributor Cultivation Program

MSCP is a "Earth Online" style role-playing game developed based on the mcpp-standard open-source project. In the game, you'll play as a "programming beginner" embarking on a challenging and exciting journey to learn Modern C++ and uncover its underlying truths...

Price:FreeDeveloper:SunrisepeakPublisher:MOGARelease Date:October 2025Game Duration:100H - 200HTags:Souls-like, The Sims, 🌍Online, Programmer, C++, Open Source, Feynman Learning Method- -> Game Details

Usage Guide

mcpp-standard is a hands-on tutorial project focused on Modern C++ core language features. Based on the xlings(d2x) tool, it implements a compiler-driven development model for code practice that can automatically detect exercise code status and navigate to the next exercise.

0. xlings Tool Installation

xlings contains the tools required for the tutorial project - More tool details

Linux

curl -fsSL https://d2learn.org/xlings-install.sh | bash

or

wget https://d2learn.org/xlings-install.sh -O - | bash

Windows - PowerShell

Invoke-Expression (Invoke-Webrequest 'https://d2learn.org/xlings-install.ps1.txt' -UseBasicParsing).Content

1. Get Project and Auto-configure Environment

Download the project to current directory and automatically configure local environment

xlings install d2x:mcpp-standard

Local E-book

Execute

d2x bookcommand in the project directory to open local documentation (includes usage guide and e-book)

d2x book

Practice Code Auto-detection

Enter the project directory

mcpp-standardand run the checker command to enter the practice code auto-detection program

d2x checker

Specify Exercise for Detection

d2x checker [name]

Note: Exercise names support fuzzy matching

Sync Latest Practice Code

Since the project is continuously updated, you can use the following command for automatic synchronization (if synchronization fails, you may need to manually update the project code using git)

d2x update

2. Automated Detection Program Introduction

After entering the automated code practice environment using xlings checker, the tool will automatically locate and open the corresponding practice code file, and output compiler errors and hints in the console. The detection program generally has two detection phases: the first is compile-time detection, where you need to fix compilation errors based on hints in the practice code and compiler error messages in the console; the second is runtime detection, which checks if the current code passes all checkpoints when running. When compilation errors are fixed and all checkpoints are passed, the console will display that the current exercise is completed and prompt you to proceed to the next exercise.

Practice Code File Example

// mcpp-standard: https://github.com/Sunrisepeak/mcpp-standard

// license: Apache-2.0

// file: dslings/hello-mcpp.cpp

//

// Exercise: Automated Code Practice Tutorial

//

// Tips:

// This project uses the xlings tool to build automated code practice projects. Execute

// xlings checker in the project root directory to enter "compiler-driven development mode"

// for automatic exercise code detection.

// You need to modify errors in the code based on console error messages and hints.

// When all compilation errors and runtime checkpoints are fixed, you can delete or comment

// out the D2X_WAIT macro in the code to automatically proceed to the next exercise.

//

// - D2X_WAIT: This macro isolates different exercises. You can delete or comment it out to proceed to the next exercise.

// - d2x_assert_eq: This macro is used for runtime checkpoints. You need to fix code errors so that all

// - D2X_YOUR_ANSWER: This macro indicates code that needs modification, typically used for code completion (replace this macro with correct code)

//

// Auto-Checker Command:

//

// d2x checker hello-mcpp

//

#include <d2x/common.hpp>

// You can observe "real-time" changes in the console when modifying code

int main() {

std::cout << "hello, mcpp!" << std:endl; // 0. Fix this compilation error

int a = 1.1; // 1. Fix this runtime error, change int to double to pass the check

d2x_assert_eq(a, 1.1); // 2. Runtime checkpoint, need to fix code to pass all checkpoints (cannot directly delete checkpoint code)

D2X_YOUR_ANSWER b = a; // 3. Fix this compilation error, give b an appropriate type

d2x_assert_eq(b, 1); // 4. Runtime checkpoint 2

D2X_WAIT // 5. Delete or comment out this macro to proceed to the next exercise (project formal code practice)

return 0;

}

Console Output and Explanation

🌏Progress: [>----------] 0/10 -->> Shows current exercise progress

[Target: 00-0-hello-mcpp] - normal -->> Current exercise name

❌ Error: Compilation/Running failed for dslings/hello-mcpp.cpp -->> Shows detection status

The code exist some error!

---------C-Output--------- - Compiler output information

[HONLY LOGW]: main: dslings/hello-mcpp.cpp:24 - ❌ | a == 1.1 (1 == 1.100000) -->> Error hint and location (line 24)

[HONLY LOGW]: main: dslings/hello-mcpp.cpp:26 - 🥳 Delete the D2X_WAIT to continue...

AI-Tips-Config: https://d2learn.org/docs/xlings -->> AI hints (requires configuring large model key, optional)

---------E-Files---------

dslings/hello-mcpp.cpp -->> Current detected file

-------------------------

Homepage: https://github.com/d2learn/xlings

3. Configure Project (Optional)

Configure Language

Edit the lang attribute in the project configuration file config.xlings. zh corresponds to Chinese, and en corresponds to English.

},

private = {

-- project private attributes

mcpp = {

lang = "en", -- option: en, zh

}

},

}

Custom Editor - Using nvim as Example

If you prefer to use Neovim as your editor with LSP (clangd) support, you can configure it as follows:

1. Edit the editor attribute in the project configuration file config.xlings and set it to nvim (or zed)

d2x = {

checker = {

name = "dslings",

editor = "nvim", -- option: vscode, nvim, zed

},

2. Run the one-click dependency installation and environment configuration command in the project root directory

xlings install

3. In the project directory, rerun the detection command d2x checker to open the corresponding exercise file with Neovim, which will support automatic exercise navigation/switching

Note: In Neovim, the "real-time detection feature" is triggered by the

:wcommand. That is, after modifying the code, saving the file in Neovim's command-line mode (:w) will promptd2xto update the detection results.

4. Resources and Communication

Communication Group (Q): 167535744

Tutorial Discussion Section: https://forum.d2learn.org/category/20

xlings: https://github.com/d2learn/xlings

Tutorial Repository: https://github.com/Sunrisepeak/mcpp-standard

Tutorial Video Collection: https://space.bilibili.com/65858958/lists/5208246

Type Deduction - auto and decltype

auto and decltype are powerful type deduction tools introduced in C++11. They not only make code more concise but also enhance the expressive power of templates and generics.

| Book | Video | Code | X |

|---|---|---|---|

| cppreference-auto / cppreference-decltype / markdown | Video Explanation | Practice Code |

Why were they introduced?

- Solve the problem of overly complex type declarations

- Need to obtain object or expression types in template applications

- Support lambda expression definitions

What's the difference between auto and decltype?

- auto is often used for variable definitions, and the deduced type may lose const or reference (can be explicitly specified with auto &)

- decltype obtains the exact type of an expression

- auto generally cannot be used as a template type parameter

I. Basic Usage and Scenarios

Declaration and Definition

Acts as a type placeholder to assist in variable definition or declaration. When using auto, the variable must be initialized, while decltype can be used without initialization.

int b = 2;

auto b1 = b;

decltype(b) b2 = b;

decltype(b) b3; // Can be used without initialization

Expression Type Deduction

Often used for complex expression type deduction to ensure calculation precision

int a = 1;

auto b1 = a + 2;

decltype(a + 2 + 1.1) b2 = a + 2 + 1.1;

auto c1 = a + '0';

decltype(2 + 'a') c2 = 2 + 'a';

Complex Type Deduction

Iterator Type Deduction

std::vector<int> v = {1, 2, 3};

auto it = v.begin(); // Automatically deduce iterator type

// decltype(v.begin()) it = v.begin();

for (; it != v.end(); ++it) {

std::cout << *it << " ";

}

Function Type Deduction

For complex types like functions or lambda expressions, auto and decltype are commonly used. Generally, lambda definitions use auto, while template type parameters use decltype.

int add_func(int a, int b) {

return a + b;

}

int main() {

auto minus_func = [](int a, int b) { return a - b; };

std::vector<std::function<decltype(add_func)>> funcVec = {

add_func,

minus_func

};

funcVec[0](1, 2);

funcVec[1](1, 2);

//...

}

Function Return Type Deduction

Syntax Sugar Usage

auto supports trailing return type function definitions and can be used with decltype for return type deduction.

auto main() -> int {

return 0;

}

auto add(int a, double b) -> decltype(a + b) {

return a + b;

}

Function Template Return Type Deduction

When the template return type cannot be determined, auto + decltype can be used for deduction, allowing add to support general types like int, double,... and complex types like Point, Vec,... enhancing generic programming expressiveness. (In C++14, decltype can be omitted)

template<typename T1, typename T2>

auto add(T1 a, T2 b) -> decltype(a + b) {

return a + b;

}

Class/Structure Member Type Deduction

struct Object {

const int a;

double b;

Object() : a(1), b(2.0) { }

};

int main() {

const Object obj;

auto a = obj.a;

std::vector<decltype(obj.b)> vec;

}

II. Important Notes - The Impact of Parentheses

Difference between decltype(obj) and decltype( (obj) )

- Generally,

decltype(obj)obtains its declared type - While

decltype( (obj) )obtains the type of the(obj)expression (lvalue expression)

int a = 1;

decltype(a) b; // Deduction result is a's declared type int

decltype( (a) ) c; // Deduction result is the type of (a) lvalue expression int &

Difference between decltype(obj.b) and decltype( (obj.b) )

decltype( (obj.b) ): Type deduction from expression perspective, obj's definition type affects deduction result. For example, if obj is const-qualified, const will limit obj.b access to const.decltype(obj.b): Since it deduces the member's declared type, it won't be affected by obj's definition.

struct Object {

const int a;

double b;

Object() : a(1), b(2.0) { }

};

int main() {

Object obj;

const Object obj1;

decltype(obj.b) // double

decltype(obj1.b) // double

decltype( (obj.b) ) // double &

decltype( (obj1.b) ) // Affected by obj1's const qualification, so it's const double &

}

Rvalue Reference Variables are Lvalues in Expressions

int &&b = 1;

decltype(b) // Deduction result is declared type int &&

decltype( (b) ) // Deduction result is int &

III. Additional Resources

- Discussion Forum

- mcpp-standard Tutorial Repository

- Tutorial Video List

- Tutorial Support Tool - xlings

Defaulted and Deleted Functions

List Initialization

List initialization is an initialization style that uses { arg1, arg2, ... } lists (curly braces) to initialize objects, and can be used in almost all object initialization scenarios, hence it's often called uniform initialization. Additionally, it adds type checking for list members to prevent narrowing issues.

| Book | Video | Code | X |

|---|---|---|---|

| cppreference / markdown | Video Explanation | Practice Code |

Why was it introduced?

- Solve the problem of inconsistent initialization syntax styles

- Prevent narrowing issues caused by implicit conversions

- Facilitate container type initialization

- Resolve default initialization syntax pitfalls

I. Basic Usage and Scenarios

Uniform Initialization Style

Before C++11, different scenarios had different initialization methods:

int a = 5; // Copy initialization

int b(5); // Direct initialization

int arr[3] = {1, 2, 3}; // Array initialization

Object obj1; // Default construction

Object obj2(obj1); // Copy construction

They can be unified in style using { }:

int a = { 5 }; // Copy initialization

int b { 5 }; // Direct initialization

int arr[3] = {1, 2, 3}; // Array initialization

Object obj1 { }; // Default initialization

Object obj2 { obj1 }; // Copy construction

Avoid Implicit Type Conversion and Narrowing Issues

Traditional initialization methods generally follow the C language implicit type conversion rules. For example, when initializing an int type variable with a double type, the decimal part is automatically discarded. List initialization adds additional compile-time type checking to avoid implicit type conversions and precision loss issues. In modern C++, unless intentional implicit type conversion is needed, using list initialization is generally a better choice.

int a = 3.3; // ok

int a = { 3.3 }; // error

constexpr double b { 3.3 }; // ok

int c(b); // ok -> 3

int c { b }; // error: type mismatch

Narrowing checks in array initialization:

int arr[] { 1, 2, 3.3, 4 }; // error: 3.3 causes narrowing

int arr[] = { 1, 2, b, 4 }; // error: b causes narrowing

Note: If b is a runtime variable, the compiler might only trigger narrowing warnings instead of errors.

Improve Container Initialization Conciseness

For container type initialization, old C++ often required two steps. First, create an element array; second, use this array to initialize the container.

int arr[5] = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5};

std::vector<int> v(arr, arr + sizeof(arr) / sizeof(int));

The introduction of list initialization allows us to combine these two steps into one, significantly improving container initialization conciseness.

std::vector<int> v1 {1, 2, 3};

std::vector<int> v2 {1, 2, 3, 4, 3};

Moreover, through std::initializer_list, our custom types can also support this variable-length list initialization style.

class MyVector {

public:

MyVector() = default;

MyVector(std::initializer_list<int> list) {

for (auto it = list.begin(); it != list.end(); it++) {

// *it ...

}

}

};

MyVector v1 {1, 2, 3};

MyVector v2 {1, 2, 3, 4, 3};

Avoid Initialization Syntax Pitfalls

Using { } to call default constructors avoids syntax pitfalls.

#include <iostream>

struct Object {

Object() { std::cout << "Constructor called!" << std::endl; }

};

int main() {

Object obj1 { };

Object obj2(); // obj2 is a function, not an Object instance

}

II. Important Notes

Array Type List Initialization

The values in array type definitions are generally indeterminate, but list initialization performs default value initialization and supports automatic zero-padding.

Regular arrays:

int arr[4]; // arr[0] indeterminate

int arr[4] { }; // arr[0] = 0

int arr[4] { 1, 2 }; // arr[2] / arr[3] automatically padded to 0

Array containers:

std::array<int, 4> arr; // arr[0] indeterminate/may be random value

std::array<int, 4> arr { }; // arr[0] == 0

std::array<int, 4> arr { 1, 2 }; // arr[0] == 1, arr[2] automatically padded to 0

Member Initialization Issues

List initialization supports direct initialization of aggregate type members, but note that after adding constructors, they must match the constructor.

struct Point {

int x, y;

// Point(int x, int y) { ... }

};

Point { 1, 2 };

Point p1 { 2, 3 }; // p1 { x: 2, y: 3}

Prefer std::initializer_list Constructors

class MyVector {

public:

MyVector() = default;

MyVector(int x, int y) { }

MyVector(std::initializer_list<int> list) {

for (auto it = list.begin(); it != list.end(); it++) {

// *it ...

}

}

};

MyVector v1 { 1, 2 }; // Prefers MyVector(std::initializer_list<int> list)

MyVector v1(1, 2); // Matches MyVector(int x, int y)

III. Additional Resources

- Discussion Forum

- mcpp-standard Tutorial Repository

- Tutorial Video List

- Tutorial Support Tool - xlings

Delegating Constructors

Delegating constructors are syntactic sugar introduced in C++11. Through simple syntax, they can avoid writing excessive repetitive code and achieve constructor logic reuse without affecting performance.

| Book | Video | Code | X |

|---|---|---|---|

| cppreference / markdown | Video Explanation | Practice Code |

Why was it introduced?

- Avoid writing repetitive code in constructor overloading

- Facilitate code maintenance

I. Basic Usage and Scenarios

Reusing Constructor Logic

When a class needs to write overloaded constructors, it's easy to end up with a lot of repetitive code, for example:

class Account {

string id;

string name;

string coin;

public:

Account(string id_) {

id = id_;

name = "momo";

coin = "0元";

}

Account(string id_, string name_) {

id = id_;

name = name_;

coin = "0元";

}

Account(string id_, string name_, int coin_) {

id = id_;

name = name_;

coin = std::to_string(coin_) + "元";

}

};

The initialization code in these 3 constructors is clearly repetitive (actual initialization might be more complex). With delegating constructor support, by using : Account(xxx) in the constructor member initialization list to delegate to other more complete constructors, we can keep only one copy of the code.

class Account {

string id;

string name;

string coin;

public:

Account(string id_) : Account(id_, "momo") { }

Account(string id_, string name_) : Account(id_, name_, 0) { }

Account(string id_, string name_, int coin_) {

id = id_;

name = name_;

coin = std::to_string(coin_) + "元";

}

};

The above two constructors, through delegation, will ultimately forward to Account(string id_, string name_, int coin_).

Why is it easier to maintain?

Suppose if the currency unit or name needs to be modified, the repetitive code implementation not only violates the reuse principle but also requires multiple modifications when changing constructor logic, increasing maintenance costs.

With delegating constructors, the constructor logic is placed in one location, making modifications and maintenance more convenient.

For example, if we need to change 元 to 原石, we only need to modify it once:

class Account {

// ...

Account(string id_, string name_, int coin_) {

//...

//coin = std::to_string(coin_) + "元";

coin = std::to_string(coin_) + "原石";

}

};

Difference from encapsulating in an init function

Some might think: if we write the constructor logic as an init function, wouldn't that also achieve code reuse? Why add a new syntax as a feature to the standard? Isn't it redundant and making C++ more complex?

class Account {

// ...

init(string id_, string name_, int coin_) {

id = id_;

name = name_;

coin = std::to_string(coin_) + "元";

}

public:

Account(string id_) { init(id_, "momo", 0); }

Account(string id_, string name_) { init(id_, name_, 0); }

Account(string id_, string name_, int coin_) {

init(id_, name_, coin_);

}

};

Actually, from a performance perspective, in most cases, separately encapsulating an init function has lower performance than delegating constructors. Because member construction generally goes through two stages:

- Step 1: Execute default initialization or member initialization list

- Step 2: Run constructor logic in the constructor body

class Account {

// ...

public:

Account(string id_, string name_, int coin_)

/* : 1 - member initialization list */

{

// 2 - execute constructor function body

init(id_, name_, coin_);

}

};

This causes members to be "initialized" twice when using an init function, while delegating constructors can avoid this problem through the member initialization list:

class Account {

// ...

public:

Account(string id_, string name_, int coin_)

: id { id_ }, name { name_ }, coin { std::to_string(coin_) + "元" }

{

// ...

}

};

II. Important Notes

Temporary Object Misunderstanding

In scenarios not using delegating constructors, calling another constructor within a constructor body actually just creates a temporary object:

- Calling a normal function

init: initializes this object's members - Calling another constructor: creates a new temporary object outside this object

class Account {

// ...

public:

Account(string id_, string name_) {

Account(id_, name_, 0); // creates a temporary object

// init(id_, name_, 0);

// this->Account(id_, name_, 0); // error

}

Account(string id_, string name_, int coin_) {

id = id_;

name = name_;

coin = std::to_string(coin_) + "元";

}

};

Cannot Reinitialize

When using delegating constructors, you cannot use the initialization list to initialize other members. This restriction avoids repeated initialization and ensures data members are only initialized once.

For example, if the following syntax were allowed, coin would be initialized multiple times and could cause ambiguity:

class Account {

// ...

public:

Account(string id_)

: Account(id_, "momo"), coin { "0元" } // error

{

}

};

III. Additional Resources

- Discussion Forum

- mcpp-standard Tutorial Repository

- Tutorial Video List

- Tutorial Support Tool - xlings

Inherited Constructors

Inherited constructors are a syntactic feature introduced in C++11 that solves the tedious problem of derived classes repeatedly defining base class constructors in class inheritance structures.

| Book | Video | Code | X |

|---|---|---|---|

| cppreference / markdown | Bili / Youtube | Practice Code |

Why was it introduced?

- Reduce repetitive code, avoid manual forwarding

- Improve code expressiveness

I. Basic Usage and Scenarios

Reusing Base Class Constructors

Before the inherited constructors feature was introduced, even when base and derived class constructors had identical forms, they still needed to be redefined. This not only caused code duplication but also lacked conciseness. For example, in the following code, MyObject reimplements each constructor from Base:

class ObjectBase {

//...

public:

ObjectBase(int) {}

ObjectBase(double) {}

};

class MyObject : public ObjectBase {

public:

MyObject(int x) : ObjectBase(x) {}

MyObject(double y) : ObjectBase(y) {}

//...

};

With this feature, you can directly inherit constructors from the base class using using ObjectBase::ObjectBase;, avoiding this manual forwarding process:

class MyObject : public ObjectBase {

public:

using ObjectBase::ObjectBase;

//...

};

It's important to note that constructor inheritance during compile-time implicit code generation is not just a "simple" copy of constructors, but also has an effect similar to "automatic renaming" in the derived class (ObjectBase -> MyObject). That is:

class MyObject : public ObjectBase {

public:

// Possible generated code

MyObject(int x) : ObjectBase(x) {}

MyObject(double y) : ObjectBase(y) {}

};

Type Functionality Extension

In many special scenarios, we might want to add additional behavior/methods to a type without changing its construction behavior. This is where inherited constructors can be used:

class ObjectXXX : public Object {

public:

using Object::Object;

void your_method() { /* ... */ }

};

When testing or debugging certain types, we often wish to use interfaces like to_string(). If modifying the source code directly is inconvenient, we can use the inherited constructors feature to create a new type with "the same interface" and add some convenient debugging interface functions, thus achieving indirect testing with more convenient debugging functions. For example, consider this Student class:

class Student {

protected:

//...

double score;

public:

string id;

string name;

uint age;

Student(string id, string name);

Student(string id, string name, uint age);

Student(string id, ...);

};

By implementing StudentDebug and adding some helper functions, it becomes easier to obtain debugging information:

class StudentDebug : public Student {

public:

using Student::Student;

std::string to_string() const {

return "{ id: " + id + ", name: " + name

+ ", age: " + std::to_string(age) + " }";

}

void dump() const { /* some score details ... */ }

void assert_valid() const {

assert(score >= 0 && score <= 100);

// ...

}

};

When using StudentDebug, both object creation and original method usage remain consistent with Student. Therefore, for requirements that only add behavior without changing the original type's object construction form, using inherited constructors can greatly simplify code.

Note: Generally, this approach can maintain the same object construction + behavior/method invocation form as the base class. However, it doesn't necessarily have the same memory layout (e.g., adding virtual methods), and type judgment (RTTI) is not equal.

Exception or Error Type Identification and Forwarding

In error and exception handling, we can define only a basic error type:

class ErrorBase {

public:

ErrorBase() { }

ErrorBase(const char *) { }

ErrorBase(std::string) { }

//...

};

When defining error types for multiple identification scenarios, using inherited constructors easily allows them to maintain the same construction form as the base error type. For example:

class ConfigError : public ErrorBase {

public:

using ErrorBase::ErrorBase;

};

class RuntimeError : public ErrorBase {

public:

using ErrorBase::ErrorBase;

};

class IoError : public ErrorBase {

public:

using ErrorBase::ErrorBase;

};

Each scenario's error corresponds to an error type, not only maintaining unified error object construction but also being well-suited for automatic error type forwarding and processing with C++'s overloading mechanism. For example, we can implement corresponding processing functions for each error type, and types without implementations will use the base type's processing function, similar to exception catching and handling designs in many programming languages. For example, a custom error processor:

struct MyErrProcessor {

static void process(ErrorBase err) { /* base processing */ }

static void process(ConfigError err) { /* config error processing */ }

// ...

};

MyErrProcessor::process(errObj); // Automatically matches corresponding error processing function

Generic Decorators and Behavior Constraints

Inherited constructors can be used not only in ordinary inheritance but also in template types. For example, in the following NoCopy definition, using T::T is used to inherit constructors from generic type T. Its purpose is to apply certain behavior constraints without changing the target object's construction form and usage interface:

template <typename T>

class NoCopy : public T {

public:

using T::T;

NoCopy(const NoCopy&) = delete;

NoCopy& operator=(const NoCopy&) = delete;

// ...

};

In some modules or scenarios, when we want objects to not be created by copying after initial creation, we can use this NoCopy decorator/wrapper during definition. The wrapper's delete explicitly tells the compiler to delete copy construction and copy assignment, meaning the object no longer has copy semantics. For example:

class Point {

double mX, mY;

public:

Point() : mX { 0 }, mY { 0 } { }

Point(double x, double y) : mX { x }, mY { y } { }

string to_string() const {

return "{ " + std::to_string(mX)

+ ", " + std::to_string(mY) + " }";

}

};

Point p1(1, 2);

NoCopy<Point> p2(2, 3);

In this case, both p1 and p2 have the same interface usage, but p2 lacks the copyable property compared to p1:

p1.to_string(); // ok

p2.to_string(); // ok

auto p3 = p1; // ok (copy construction)

auto p4 = p2; // error (cannot copy)

II. Important Notes

Prefer Inheritance or Composition

Since this chapter introduces the inherited constructors feature and usage, it's bound to the inheritance nature. Therefore, implementation-wise, it tends to use inheritance. However, considering the target functionality, both inheritance and composition can often achieve the goal; they are more like means rather than ends, so the choice should be based on specific application scenarios.

For example, for testing environments or scenarios involving only functional extension without data structure changes, using inheritance with inherited constructors is more convenient and can avoid extensive function forwarding. However, for scenarios requiring "interception" of specific interfaces or more complex situations, the mainstream approach (as of 2025) tends to prefer composition over inheritance.

- Complex scenarios or requiring an intermediate layer for special processing -> generally composition is better than inheritance

- Simple functional extension requiring consistent interface usage -> generally inheritance is better than composition

III. Practice Code

Practice Code Topics

- 0 - Familiarize with Inherited Constructors Feature

- 1 - Application in Functional Extension - StudentTest

- 2 - Application in Generic Templates - NoCopy / NoMove Behavior Constraints

Practice Code Auto-detection Command

d2x checker inherited-constructors

IV. Additional Resources

- Discussion Forum

- mcpp-standard Tutorial Repository

- Tutorial Video List

- Tutorial Support Tool - xlings

nullptr - Pointer Literal

nullptr is a pointer literal introduced in C++11, used to represent null pointers. It addresses the shortcomings of traditional null pointer representations (such as NULL and 0) in terms of type safety and overload resolution.

| Book | Video | Code | X |

|---|---|---|---|

| cppreference / markdown | Video Explanation | Practice Code |

Why was it introduced?

- Resolve ambiguity issues with

NULLmacro and integer0in overload resolution - Provide type-safe null pointer representation

- Clearly distinguish between pointer and integer types

- Support type deduction in template programming

What's the difference between nullptr and NULL?

nullptris a keyword introduced in C++11, with typestd::nullptr_tNULLis a preprocessor macro, typically defined as integer0or(void*)0nullptris more precise in overload resolution and won't be confused with integer types

I. Basic Usage and Scenarios

Replacing NULL and 0

Used for pointer variable initialization and assignment, replacing traditional

NULLand0

int* ptr1 = nullptr; // Recommended usage

int* ptr2 = NULL; // Traditional usage

int* ptr3 = 0; // Not recommended

// Check if pointer is null

if (ptr1 == nullptr) {

// Handle null pointer case

}

Resolving Overload Ambiguity

Explicitly passing null pointers in function calls,

nullptrcan avoid overload ambiguity issues and prevent confusion with integer types

void func(int* ptr) {

if (ptr != nullptr) {

*ptr = 42;

}

}

void func(int value) {

// Handle integer parameter

}

int main() {

func(nullptr); // Explicitly call pointer version

func(0); // May call integer version, causing ambiguity

func(NULL); // May call integer version, causing ambiguity

}

For example, in the code above, calling func(NULL) will report an overload ambiguity error

main.cpp: In function 'int main()':

main.cpp:16:9: error: call of overloaded 'func(NULL)' is ambiguous

16 | func(NULL); // May call integer version, causing ambiguity

| ~~~~^~~~~~

Ensuring Type Safety in Template Programming

In template functions and classes,

nullptrprovides better type deduction and safety

// https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/language/nullptr.html

template<class T>

constexpr T clone(const T& t) {

return t;

}

void g(int*) {

std::cout << "Function g called\n";

}

int main() {

g(nullptr); // ok

g(NULL); // ok

g(0); // ok

g(clone(nullptr)); // ok

g(clone(NULL)); // ERROR: NULL might be deduced to non-"pointer" type

g(clone(0)); // ERROR: 0 will be deduced to non-"pointer" type

}

When using function templates, NULL and 0 are usually deduced to non-"pointer" types, while nullptr can avoid this problem

main.cpp:19:12: error: invalid conversion from 'int' to 'int*' [-fpermissive]

19 | g(clone(0)); // ERROR: 0 will be deduced to non-"pointer" type

| ~~~~~^~~

| |

| int

Smart Pointers and Containers

Used with modern C++ features (such as smart pointers, STL containers)

#include <memory>

#include <vector>

int main() {

std::shared_ptr<int> sp1 = nullptr;

std::unique_ptr<int> up1 = nullptr;

std::vector<int*> vec;

vec.push_back(nullptr);

// Check if smart pointer is null

if (sp1 == nullptr) {

sp1 = std::make_shared<int>(42);

}

}

II. Important Notes

Type Deduction and std::nullptr_t

The type of nullptr is std::nullptr_t, which is a special type that can be implicitly converted to any pointer type:

#include <cstddef> // Contains definition of std::nullptr_t

void func(int*) {}

void func(double*) {}

void func(std::nullptr_t) {}

int main() {

auto ptr = nullptr; // ptr's type is std::nullptr_t

func(nullptr); // Call std::nullptr_t version

func(ptr); // Call std::nullptr_t version

int* intPtr = nullptr;

func(intPtr); // Call int* version

}

Implicit Conversion to Boolean Type

nullptr can be implicitly converted to bool type, which is very convenient in conditional checks:

int* ptr = nullptr;

if (ptr) { // Equivalent to if (ptr != nullptr)

// Pointer is not null

} else {

// Pointer is null

}

bool isEmpty = (ptr == nullptr); // true

III. Practice Code

Practice Code Topics

- 0 - nullptr Basic Usage

- 1 - nullptr Function Overloading

- 2 - nullptr Advantages in Template Programming

Auto-Checker Command

d2x checker nullptr

IV. Additional Resources

- Discussion Forum

- mcpp-standard Tutorial Repository

- Tutorial Video List

- Tutorial Support Tool - xlings

long long - 64-bit Integer Type

long long is a 64-bit integer type introduced in C++11, used to represent larger range integer values. It solves the range limitation issues of traditional integer types when representing large integers.

| Book | Video | Code | X |

|---|---|---|---|

| cppreference / markdown | Video Explanation | Practice Code |

Why was it introduced?

- Solve the insufficient range of traditional integer types

- Provide a unified 64-bit integer type standard

What's the difference between long long and traditional integer types?

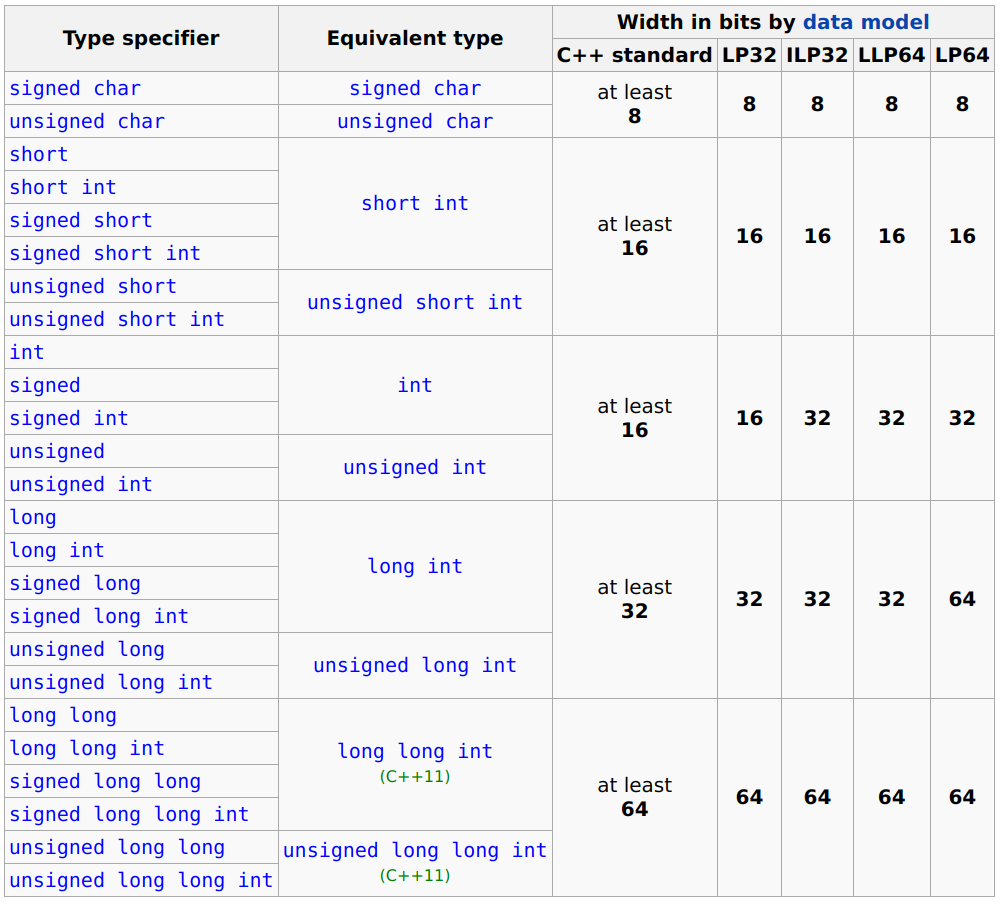

long longguarantees at least 64-bit width, with range at least from -2^63 to 2^63-1intis typically 32-bit, with range approximately -2.1 billion to 2.1 billionlongis 32-bit on 32-bit systems, typically 64-bit on 64-bit systems (but standard only guarantees at least 32-bit)

I. Basic Usage and Scenarios

Basic Declaration and Initialization

Support for signed and unsigned versions, with literal suffixes

// Signed long long

long long val1 = 1;

long long val2 = -1;

// Unsigned long long

unsigned long long uVal1 = 1;

// Literal identifiers + type deduction

auto longlong = 1LL;

auto ulonglong = 1ULL;

Large Integer Applications and Boundary Values

Handle calculations beyond traditional integer type ranges, based on boundary value acquisition

//#include <limits>

// Using long long for large number calculations (exceeding int range)

long long population = 7800000000LL; // World population

// Get integer type boundaries

int maxInt = std::numeric_limits<int>::max();

long long maxLL = std::numeric_limits<long long>::max();

auto minLL = std::numeric_limits<long long>::min();

II. Important Notes

Type Deduction and Literal Suffixes

Use LL or ll suffix to explicitly specify long long literals, use ULL or ull to specify unsigned versions

auto num1 = 10000000000; // Type may be int or long, depending on compiler

auto num2 = 10000000000LL; // Explicitly long long to assist type deduction

Type Conversion and Precision Issues

Be aware of precision loss that may occur during conversions between different integer types

long long bigValue = 3000000000LL;

int smallValue = bigValue; // May overflow

std::cout << "bigValue: " << bigValue << std::endl;

std::cout << "smallValue: " << smallValue << std::endl; // May be incorrect

// Safe conversion check

if (bigValue > std::numeric_limits<int>::max() || bigValue < std::numeric_limits<int>::min()) {

std::cout << "Conversion would cause overflow!" << std::endl;

}

Bit-Width Confusion - Why Doesn't the Standard Fix the Bit Width?

Reasons

- Hardware Variations: Different architectures have different "natural word sizes," such as 16/32/64 bits, and many embedded systems only support 8/16-bit multiplication and division instructions. If

longwere forcibly defined as 64 bits, it would cause significant performance issues on some machines (e.g., 32-bit MCUs).- For example: Performing 64-bit calculations on an 8-bit machine without relevant hardware instructions would require algorithmic simulation, leading to a sharp increase in

instruction cycles.

- For example: Performing 64-bit calculations on an 8-bit machine without relevant hardware instructions would require algorithmic simulation, leading to a sharp increase in

- Historical and ABI Compatibility: C/C++ predates the widespread adoption of modern 32/64-bit systems. Many platforms have system interfaces, file formats, and calling conventions that have already encoded the size of

int/longinto their ABI. Forcing a change in the standard would break binary compatibility and disrupt the ecosystem. - Zero-Cost Abstraction: The C/C++ standard is designed to map efficiently to the underlying hardware. It only specifies behavior and minimum ranges, allowing implementations to choose the most natural width for the platform, thereby achieving zero-cost or near-zero-cost abstraction.

Solutions

- Optional Fixed-Width Types in C/C++: When precise bit widths are required, use types from

<cstdint>/<stdint.h>such asint8_t,int16_t,int32_t,int64_t, etc. - Avoid Bit-Width Assumptions and Use Static Assertions: Avoid assuming the bit width of types during development to improve portability. If certain code relies on specific bit-width assumptions, use static assertions to ensure the width meets expectations:

static_assert(sizeof(T) == N).

III. Practice Code

Practice Code Topics

Auto-Checker Command

d2x checker long-long

IV. Additional Resources

- Discussion Forum

- mcpp-standard Tutorial Repository

- Tutorial Video List

- Tutorial Support Tool - xlings

Type alias and alias template

Type alias and alias template are important features introduced in C++11, used to create new names for existing types, enhancing the expressive power of generic programming, and improving code readability and maintainability.

| Book | Video | Code | X |

|---|---|---|---|

| cppreference-type-alias / markdown | Video Explanation | Exercise Code |

Note: The

usingkeyword existed before C++11, but was mainly used for namespace and class member declarations

- Declaring namespaces:

using namespace std;- Class member declarations:

struct B : A { using A::member; };

Why introduced?

- Replace traditional

typedefsyntax with a more intuitive way to define type aliases - Support template aliases, enhancing the expressive power of generic programming

- Improve code readability, especially for complex types

- Consistent with

usingdeclaration syntax

What's the difference between type alias and typedef?

- More intuitive syntax:

using NewType = OldType;vstypedef OldType NewType; - Support template aliases, while

typedefdoes not - More flexible and powerful in template programming

I. Basic Usage and Scenarios

Basic Type Alias

Create new names for existing types to improve code readability, and can replace traditional

typedefalias definitions

typedef int Integer; // Traditional typedef way

using Integer = int; // C++11 using way

// Using aliases

Integer i = 1;

int j = 2;

Type alias is not a new type, but an alias for other composite types, essentially the same. In the above code, the essence of Integer is int, commonly used to simplify type names.

Complex Type Alias

Create aliases for complex types (such as function pointers, nested types)

// Function pointer alias

using FuncPtr = void(*)(int, int);

using StringVector = std::vector<std::string>;

// Nested type alias

struct Container {

using ValueType = int;

using Iterator = std::vector<ValueType>::iterator;

};

void example(int a, int b) {

// Function implementation

}

int main() {

FuncPtr func = example; // Equivalent: void(*func)(int, int) = example;

StringVector strings = {"hello", "world"}; // Equivalent: std::vector<std::string> strings...

Container::ValueType value = 100; // Equivalent: int value = 100;

return 0;

}

For code like void (*func)(int, int) = example;, many people might hesitate before understanding it defines a function pointer. By using using to give complex types a type alias FuncPtr, using FuncPtr func = example; allows people to quickly understand the code's intent.

Alias Template

Create aliases for template types, enhancing generic programming capabilities

// Alias template

template <typename T>

using Vec = std::vector<T>;

// Create "subset" alias types based on generics

template <typename T>

using Vec3 = std::array<T, 3>;

template <typename T>

using Vec4 = std::array<T, 4>;

// Alias template with default parameters

template <typename T, typename Compare = std::less<T>>

using Heap = std::priority_queue<T, std::vector<T>, Compare>;

int main() {

Vec<int> numbers = {1, 2, 3};

Vec3<float> v3 = {1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f};

Vec4<float> v4 = {1.0f, 2.0f, 3.0f, 4.0f};

Heap<int> minHeap;

Heap<int, std::greater<int>> maxHeap;

return 0;

}

In addition to creating aliases for complex types, it also supports creating aliases for template types, and through template parameters, it can control the parameters/properties of the original template type - default parameters, allocator types, length, comparators, etc. In the above code, we created dynamic Vec type aliases; also created fixed-length Vec3, Vec4 type aliases for special scenarios (vector, matrix calculations) by specifying length; and used template parameter defaults to create Heap type, using vector as the underlying data structure by default, supporting default min-heap, and setting max-heap by specifying template parameters.

Standard Library _t Style Templates

In STL, some templates provide _t versions to save the process of manually obtaining types and values. Type aliases can easily implement them. _v style suuport by

c++ 17[inline variables + variable templates]

Reference implementation of std::remove_const_t

// Implementation and principle explanation of remove_const can refer to: https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/352972564

template <typename T>

using my_remove_const_t = typename std::remove_const<T>::type;

int main() {

const int a = 10;

my_remove_const_t<decltype(a)> b = a; // b's type is int, not const int

return 0;

}

II. Precautions

Alias is Not a New Type

Type alias is just a synonym for existing types and does not create new types

using MyInt = int;

using YourInt = int;

int main() {

MyInt a = 10;

YourInt b = 20;

a = b; // Can assign because both are int types

static_assert(std::is_same<MyInt, YourInt>::value, "Types are the same");

return 0;

}

Scope of Template Aliases

Alias templates must be declared at class scope or namespace scope

namespace MyNamespace {

template<typename T>

using MyVector = std::vector<T>;

}

class MyClass {

public:

template<typename T>

using Ptr = T*;

};

// Error: cannot declare alias template in function scope

// void func() {

// template<typename T>

// using LocalAlias = T; // Compilation error

// }

Recursive Alias Restrictions

Alias templates cannot directly or indirectly reference themselves

template<typename T>

struct A;

// Error: recursive alias

// template<typename T>

// using B = typename A<T>::U;

template<typename T>

struct A {

// typedef B<T> U; // This will cause recursive definition error

};

III. Exercise Code

Exercise Code Topics

- 0 - Basic Type Alias

- 1 - Complex Types and Function Pointer Aliases

- 2 - Alias Template Basics

- 3 - Alias Template Applications in Standard Library

Exercise Code Auto-Check Command

d2x checker type-alias

IV. Other

- Discussion Forum

- mcpp-standard Tutorial Repository

- Tutorial Video List

- Tutorial Support Tool - xlings

mcpp-standard Changelog

2025/11

C++11 - 13 - long long - 64-bit Integer Type

C++11 - 12 - nullptr - Pointer Literal

2025/09

C++11 - 11 - Inherited Constructors

2025/08

C++11 - 11 - Inherited Constructors

C++11 - 10 - Delegating Constructors

Practice Detection Command

d2x checker delegating-constructors

Frequently Asked Questions

More questions and feedback -> Tutorial Forum Discussion Section